testing the new F2 tandem prototype on

Washingtons wild Ozette coast

Leann and I arrived at Neah Bay at 1pm the day before summer solstice. After a few hours of sorting food and packing gear we were ready to launch.

3pm might not be the best time to launch an untested kayak onto a rock studded fogbound coastline in the wind and drizzle, but we did still have six hours of daylight, the swell was low, and we at least had a reasonable suspicion of finding an isolated beach to land on before dark set in.

Leann discovered this useful map hanging on the side of the marina. It's tempting to chuckle at the lack of pertinant navigational details...

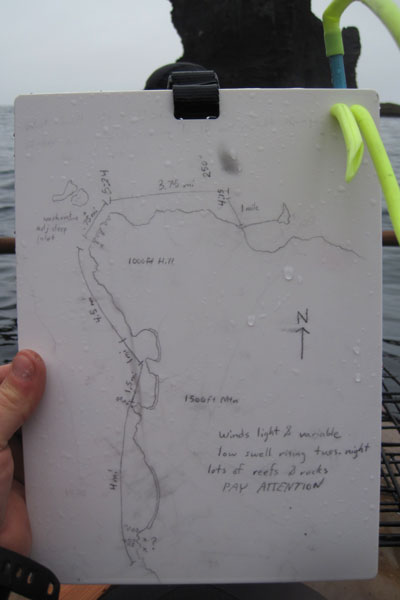

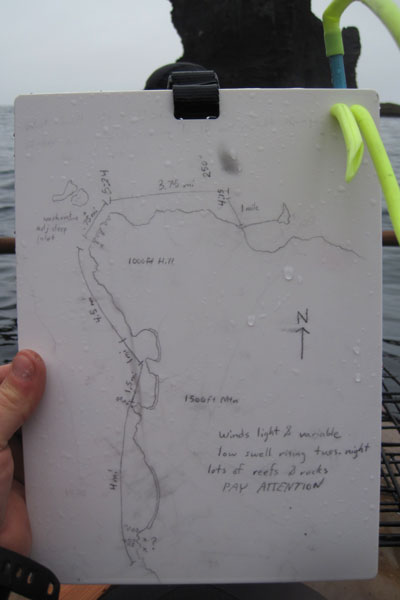

...until you see my own map, drawn freehand from Google Earth the night before! I'm sure the sight of this 'map' is currently triggering fits in a good number of people right now, so let me take a moment to clarify that after a lifetime of following coastlines I've found these simple hand drawn maps more useful than a stack of charts, current tables, newfangled GPS units, and radios. Relying on electronics for rescue or to bring you to port safely is always a mistake, and the mesmerizing amount of information on good chart/topo combo map can obsfucate the relevant details especially when trying to read on the fly while sloshing around in a six foot chop. By redrawing the map yourself, you insure that you are actually looking at the charts, considering what is relevant and important, and organizing all the information from 3 or 4 different sources in once easy to reference place. Premarked distances combined with on the water bearings and timechecks create a powerful tool to gain a clear picture about where you are and where you need to go next, which is the essence of navigation. Would I reccomend making a map off of google earth and not bringing along paper charts? No. But then again, I wouldn't recommend driving in a car, ever. (at least not with me driving) So I suppose our determinations of acceptable risk lie more in perception than analysis.

Our six mile paddle out to Cape Flattery, the most Northwestern point of the United States, was beautiful, if not a bit dark and dismal. We sloshed back and forth in a boisterous cross chop against a backdrop of jutting rock, caves, and arches while we searched for a suitable beach to land on. With low swell predicted to drop even further, it was safe to consider some fun options that could be hazardous in other circumstances.

This marvelous and mysterious tunnel led to an curiously illuminated beach and is definately one of the neater landings I've ever made in a sea kayak.

After landing I took a moment to look over the rudder assembly to see that everything was still attached and functional. A rudder is a level of fuss and expense that doesn't usually make sense on a skin-on-frame kayak, even on a day tripping double, but for a touring, sailing, double it's a useful addition.

Our bow setup. The sail has a few strings but everything is clean and stows tidily. The fishing pole is kept ready for checking out those nearshore rocks that only kayakers can access.

A stunning campsite, albeit one of dubious legality and even more dubious tidal activity. There was some debate that we may actually be camping underwater.

Our view to the North. At first I was a little dissapointed with the fog and rain, but after a while it seemed appropriate to see this place against a palate of gray.

The entire headland is a giant rock swiss chesse and would be a marvelous place to explore with a whitewater kayak on a flat day.

Leann is happy to be cozy and dry!

Recieving over a hundred forty inches of rain a year in the coastal valleys, the Olympic Peninsula is an explosion of chloropyl.

Lush growth continues all the way to the tideline.

The next morning we discovered that no spoons had made it into our bags, luckily there were plenty of natural substitutes, already cracked open and well cleaned by the maurading raccoons that raided the rocks at low tide.

The mussel shells proved to be excellent utensils and caused one to wonder at the expense, effort, and pollution of making plastic or metal silverware.

Early morning revealed that our cave beach was now rock.

A few more hours brought the water back up to the sand though and after some stretches we were once again paddling south.

Well, paddling south for about 40 yards before stopping to explore this next cool cove.

As a connoisseur of fine coastlines across the globe I'm not quite sure how Cape Flattery has escaped me for so long. It's one of those things I always meant to do but just never got around to.

A typical scene on the Cape.

The entire trip we paddled in and out of heavy fog, which is quite manageable if not a little confusing, with a very low swell with no wind, but could easily become extremely dangerous with even a moderate swell and normal onshore daily wind pattern. The prediction of no wind and a falling 3ft swell for the first 3 days was the reason I chose to do this trip at all, and even then, the final decision wasn't made until the night before we launched.

You'd think we'd know better, but we packed the hats away. Of course the fog broke, neccesiting this tricky unpacking manuever miles from land.

A glassy flat ocean and a little help from some improvised water wings makes these shennanigans possible. By the way, yes, those are our life jackets piled on deck, and yes, if a tornado or a great white suddenly hit us we might be in real trouble, but considering the conditions it was much more comfortable without them. I would only do this on a dead flat day.

A two hour crossing brought us to a beautiful cove protected by two long reefs extending out to sea.

A relatively short 12 mile day and we were both tired which really surprised me. I thought that after a winter of hardcore whitewater paddling I'd be an animal, instead all that hard anerobic paddling made me less strong over the long haul, and of course I whined about it constantly. Leann kicked back while I dropped a line in search of dinner.

A few minutes of jigging and I reeled up this Ling Cod, which I promptly filleted on deck and stuffed the carcass into a crab trap. Decades of overfishing has brought a precipitous decline to the bottomfish populations of the pacific northwest, so nowadays the only fish I will retain are Ling Cod and Black Rockfish. While looking every bit as prehistoric and horrible as their spiniest rockfish bretheren, Lings are actually a different species that grow much faster and are much more resilient, Black Rockfish are also relatively resilient, although their numbers are a fraction of historic levels.

Barely a ripple penetrated the reefs and we glided to a calm landing on a pebble beach.

Leann spotted this marvelous little rocky nook, and the best part... cobbles! Anyone who has spent time camping on sand will tell you it is a vile and insidious substance to be avoided at all costs.

Priority number one: set up tent. Priority number two: Nap!

Who needs tent stakes? "Consider the advantage..." I told Leann, "If the tide does come up in the night, at least we'll know where the boat is!"

Just when you think you've found some privacy, the locals show up!

As the sun dipped lower we set out to explore.

Leann cooked us good food while I searched for meat to compliment the meals. Pesto pasta and fresh Ling Cod for dinner. (we didn't catch any crabs!)

Our spoons proved useful vessels for the after dinner drinks, and their precarity conviently limited our intake levels, in other words, when you can't hold the shell level anymore, you're cut off!

An idyllic evening scene on the Ozette coast.

Rather suddenly, we were beset by pea soup fog, this photo was take fifteen minutes after the photo above it.

Even with the tide right at the edge of our camp, I stubbornly refused to move the tent. I liked our little spot!

Leann is skeptical of the rising waters.

Does it seem a little weird to you that we hang our food in the trees to keep the bears from eating it, while we sleep on the ground....

Our not so big beach at twilight.

Morning rituals, breakfast, packing up....

...and filling the water bottles.

Almost ready to shove off.

We set out late in the morning toward Ozette island with a very low cloud ceiling.

We detoured a ways offshore to explore a couple little islands teeming with growling stellar sea lions. A loud snort and a splash close to the boat was enough to warn us off. It may seem ridiculous, but we're talking about a habitually aggressive animal the size of fully grown Rhinocerous. Anyone who claims not to be afraid of such creatures has not yet had one rise out the water five feet from ones face, snarling and shaking thier head and baring four inch long teeth. It's an instinctively horrifying feeling when you are sitting in a kayak. These are not seals.

The less choice real estate is left to the cormorants. I always feel bad for cormorants, often seen standing with open arms to dry their perrenially wet wings. Cormorants do in fact have oil secretion glands but unlike other sea birds, they don't seem to work very well.

The fog ceiling decended forcing us to paddle south close in through the nearshore reefs and kelp beds. This tactic was only made possible by the almost completely flat seas and lack of wind. The kelp made for slow going, but did afford us a magical passage through the treetops of these rich underwater forests.

Curious sea otters monitored our passing.

In the distance Leann spotted two bald eagles perched on a spire and we paddled over for a closer look.

We bashed into a few rocks working our way back out of the reef in the swell, but nothing damaging, and absolutely worth our intimate experience with the kelp beds.

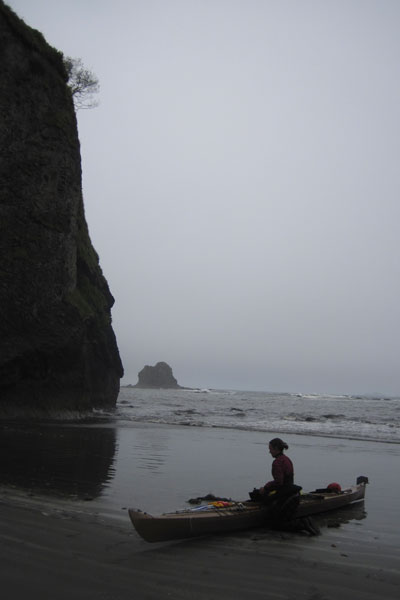

Another hour of paddling and some irritating detours around long reefs brought us to what I thought might be a good landing place for the evening. The problem was that with no visibility, we had no way to be certain that we were indeed exactly where we thought we were, and exact is what is needed when you are talking about threading through breaking waves and reefs to hit a 100 foot wide sandy slot. Whereas more heroics and dicey recon missions are possible in a single kayak, the inherent sluggishness and unlikelieness of a successful combat roll in a tandem kayak means you have to be a lot more certain before committing. We decided to sit offshore and fish while we waited for a break in the visibility.

This positively enormous, (and positively unlucky) black rockfish is now headed for the deep six in the crab trap.

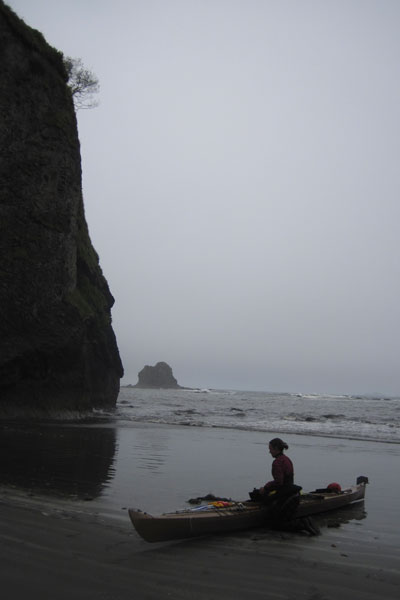

When the fog lifted I felt pretty proud that we were in fact exactly where I thought we were and all that was required was to land on this tiny sand hook, protected from the swell by a small curving reef. Much of this coast looks like a beach but is in fact a gauntlet of hard nearly submerged rock with a sloping beach above and behind it. With limited visibility such sights might tempt a kayaker to land in marginal conditions only to realize too late in the surf that there is no sand at all, possibly leading to less than pleasant outcomes.

We were soon engaged in the time honored tradition of salami, cheese, and triscuits. I was so happy to see the triscuits and greatly appreciated Leann bringing them instead of Rye Vita or some other such hippy dog biscuits.

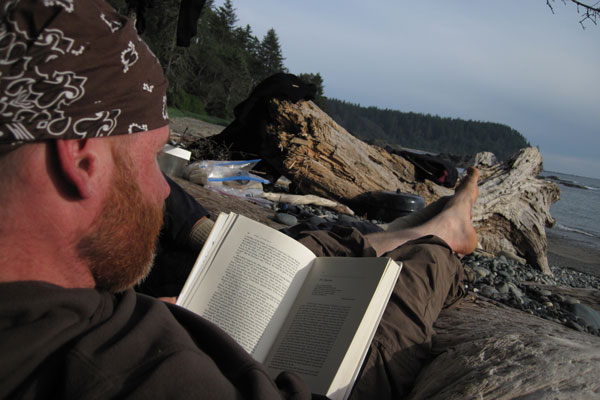

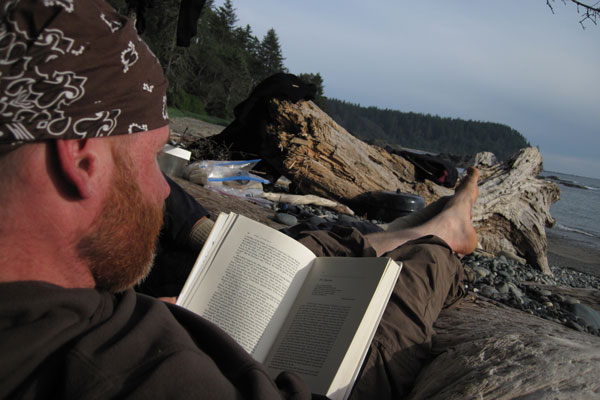

Leann insisted that we bring Watership Down, a classic, extremely well written, and extremely boring book about an exodus of talking rabbits.

"I know it's going to suck." I said, "Nothing is going to blow up, and nobody has sex."

"Rabbits have sex." Leann countered.

I begrudgringly left the sci-fi at home, and predictably we trudged through about 15 pages of Watership Down in five days. Luckily we still have 200 hundred more pages to read on future trips. Do you hear that Leann? We're going to read the whole thing!

Feeling hopeful I headed back out to check the crab trap.

...and with dashed hopes I returned empty handed. I have never pulled an empty pot on a sandy beach and was feeling quite perplexed.

I suppose if thats the worst of your problems though, life ain't too shabby.

This entire coastline is managed by the national park service and while our trip may have been, um, less than officially sanctioned, I do try to keep within the spirit of their regulations by having no open fires and leaving no trace of our campsites. I have found it difficult over the years to coordinate touring on open coastines with governing agencies. With possible landings and schedules determined by the terrain and the mood of the sea, sticking to official campsites is often not possible. Still, I try to be respectful and keep a low profile.

After a dinner of rockfish fried in butter and garlic, and a few shells of single malt, we have strawberries and chocolate brownies for dessert.

A crack in the clouds gives us a glimpse of sunset.

The next morning we rise before dawn in hopes of early visibility and putting on some miles in a rising swell.

The little line of offshore rocks functioned exactly as I'd hoped, leaving us a small clean slot to escape past what were now significant waves thundering across the reefs.

Making miles before 7am. With the first pulses of a long period seven foot swell arriving, the breakers were anything but benign and we had to keep well offshore to avoid being dashed to splinters on the reefs.

Under beautiful skies we approached Jagged Island, a fantastic rocky pinnacle jutting up like a minature Tahiti. Even with the beautiful sunshine, I watched to the west like a hawk as a low lying fog bank snuck towards us, and to the east I constantly assessed and re-assessed possible emergency landing options through the now white and surging reefs. Five minutes after this photo was taken we were working our way slowly through some reefs when I saw Jagged island suddenly dissapear to my right. We made a quick decision to crash land on a semi-protected beach in the swell shadow of Jagged island, and after a dicey slalom through some boomers we touched down with a minimum of violence on a minimal beach.

This photo was taken ten minutes after the photo above it. We would not have been able to thread the reefs in this fog and just barely made it through them before everything went white. It should be noted that another option would be to paddle well offshore and head south on a known bearing for a known time and then hang a left for shore. This works well on less varigated coastlines with wide and less consequential targets. The North Washington coast however, is a minefield of offshore reefs and rocks that extends for miles offshore. After an hour or two of traveling a complicated course in zero visibility fog by compass and watch alone, with wind and current effects, even the best orienteering bad-ass might be a little intimidated to turn shoreward to hit a narrow landing target through reefs and boomers big enough to break boats and paddlers. Now consider that sea fog often comes with a 20+ knot wind and 6ft wind chop on top of whatever existing swell there is and you get an idea of the very real danger that exists in common conditions on this coastline. The point I am trying to make is that open coast touring, especially here, requires sound judgement and careful selection of conditions. Traveling should be limited to visible passages with a careful eye toward the ever present fog banks.

It became quickly apparant that our entire beach would be awash in the quickly rising tide, so we climbed over this ridge to consider the prospects of the next beach to the North.

This thin ridge connecting an small offshore pinnacle gave me the feeling of Macchu Picchu in the fog. We saw the next beach over to have slightly more real estate including a few cobbles, so we decided to punch out around the corner for greener, or um, grayer pastures.

Rather than wait for the tide to start sloshing us around with the driftwood we dragged the boat back to the tideline and headed around the corner.

Our new digs on the other side of the rock.

The mist blew in and out revealing errie glimpses of Jagged island.

We were barely settled when this curious young buck wandered down to see who we were.

With nothing else to do while the fog swirled in and out, Leann took a nap while I explored the beaches.

The beaches are always a facinating repository for various marine trash.

I especially liked this toilet seat cover.

I have no clue what this tiny thing and can only speculate it's the scalp of a member of a previously undiscovered secretive race of seven inch tall wild coast people. I know it's these little guys who stole my car keys, and my fork, and my bandanna, and my fillet knife, and my surf hood...

Twisted kelp mats stretched up the beach like an H.R. Giger painting.

The fog swept in and out but by the afternoon it seemed to be holding so we decided to try to make the seven mile hop to La Push.

Twice we passed by what I thought was a kelp bed and Leann thought were sea birds. We were both wrong, these were giant rafts of sea otters!

Even well offshore cutting behind the reefs to avoid mile long detours proved a sketchy proposition. I don't try to capture much of this action with the camera because it never looks all that exciting. For instance, the rock above is the size of a house for scale and exploded in mass of spray and fury every 10 seconds. Moments after this shot was taken we were lifted fifteen feet up by a set wave that was threatening to break on what we assumed was a deep slot. We punched the foamy white top and dropped into a series of menacing troughs as we sprinted hard straight out to sea!

Two miles from La Push in 5 knots of wind I asked Leann to raise the sail so I could get a photo. It's a wonderful little sail, made by Mick MacRobb of Flat Earth Kayak Sails. Easy to deploy, the lines and sail fold unobtrusively onto the deck, and doesn't actually need a rudder. I'm looking forward to using it to troll offshore for salmon this summer.

We paddle past little James Island on our way into La Push. The harbor here conveniently uses James and little James as extensions of their breakwater to create a navigable channel.

We paddle upriver against the current and into the marina...

...where we feel a bit shellshocked by the sudden contrast of civilization. We float aimless and indecisive for a few minutes looking for a place to tie up.

Not wanting to bother the absent harbormaster in this sleepy town we took a chance and just tied up inside the gas dock.

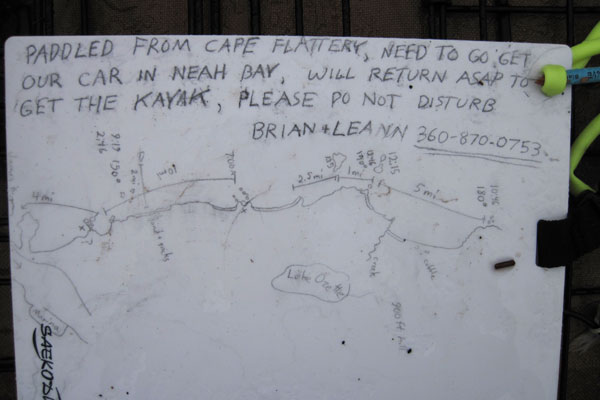

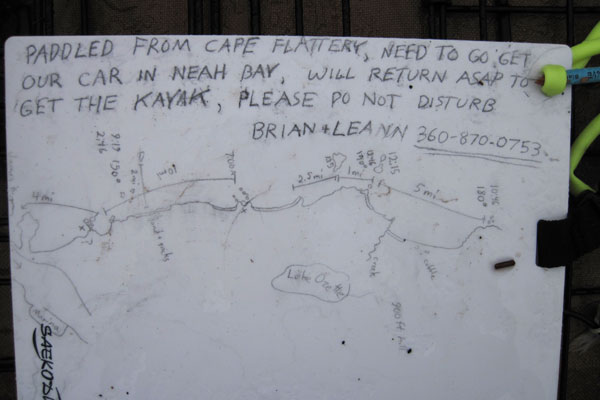

We stowed our expensive gear as best as we could and left this note for anyone who might come by. Some people might be apprehensive to leave so much gear unattended but I've found over the years that most people are more honest than you'd think. This being the the Quilleute Indian Reservation and me being a white guy, I supposed that even if the whole boat went missing I would just consider it reparations.

It was 6:30 pm and drizzling when we decided to embark on the 70 mile, 3 road hitchike back to Neah Bay. We set out with little more than street clothes and a quarter bottle of whiskey, figuring that at worst we might have an unpleasant night, but were not likely to die from it. Our first ride was the Quilleute shuttle, a free bus to forks!

Luckily they weren't enforcing the rules that day.

With the exception of the sunscreen caked onto my skin, we actually looked pretty tidy. I hitchike shuttles a lot and being clean and smiling is the first rule to getting a ride. You see a lot of hitchikers out there who look like Charles Manson, do these guys really think that they are going to get rides?

The shuttle brought us to 101, where we caught a ride north with a mountain climber who dropped us off on the very sleepy junction to 113. After walking this road for a half mile with no cars passing by we were starting to wonder if this was a bad idea when a Makah tribal councilman pulled over and gave us a ride to all the way to Neah Bay. Micah was a bright fellow and deeply involved in ocean resource issues so we had a lot to talk about on the long ride.

On our way out of Neah Bay we stopped to check out these impressive blue totem people.

Finally we arrived back at La Push at dusk, making for a very long day. Noone had bothered our kayak and we collapsed into a hard sleep feeling very grateful to have been lucky enough to see this beautiful stretch of coastline with favorable conditions, and a bit of luck when it mattered. The F2 prototype performed beautifully on the trip and it was a pleasure to use a tool so perfectly fitted to both the bodies of Leann and I and also customized for our needs. I think that this ease in changing even the hull shape for a single boat, even for a single trip, is what makes skin-on-frame so appealing to me. The challenge of course is knowing what to change and how to do it to achive a predictable result. Things don't always work out so well on a prototype, but in this case, everything functioned as intended which left me feeling pretty good. Kayaking for me is all about intimacy, the ability to get close to a remote coastline and really experience the place without a lot of fuss. A custom kayak takes that one step farther, allowing the kayak to dissapear as much as possible beneath you (but hopefully not literally!) so there is even less between you and the experience. This applies to any custom kayak really, skin-on-frame is just fun because it is such a fast, cheap way to get on the water. Even after building and helping to build well over 300 kayaks, I still get a lot of pride from saying I built it myself!

Back to Cape Falcon Kayak

Leann and I arrived at Neah Bay at 1pm the day before summer solstice. After a few hours of sorting food and packing gear we were ready to launch.

3pm might not be the best time to launch an untested kayak onto a rock studded fogbound coastline in the wind and drizzle, but we did still have six hours of daylight, the swell was low, and we at least had a reasonable suspicion of finding an isolated beach to land on before dark set in.

Leann discovered this useful map hanging on the side of the marina. It's tempting to chuckle at the lack of pertinant navigational details...

...until you see my own map, drawn freehand from Google Earth the night before! I'm sure the sight of this 'map' is currently triggering fits in a good number of people right now, so let me take a moment to clarify that after a lifetime of following coastlines I've found these simple hand drawn maps more useful than a stack of charts, current tables, newfangled GPS units, and radios. Relying on electronics for rescue or to bring you to port safely is always a mistake, and the mesmerizing amount of information on good chart/topo combo map can obsfucate the relevant details especially when trying to read on the fly while sloshing around in a six foot chop. By redrawing the map yourself, you insure that you are actually looking at the charts, considering what is relevant and important, and organizing all the information from 3 or 4 different sources in once easy to reference place. Premarked distances combined with on the water bearings and timechecks create a powerful tool to gain a clear picture about where you are and where you need to go next, which is the essence of navigation. Would I reccomend making a map off of google earth and not bringing along paper charts? No. But then again, I wouldn't recommend driving in a car, ever. (at least not with me driving) So I suppose our determinations of acceptable risk lie more in perception than analysis.

Our six mile paddle out to Cape Flattery, the most Northwestern point of the United States, was beautiful, if not a bit dark and dismal. We sloshed back and forth in a boisterous cross chop against a backdrop of jutting rock, caves, and arches while we searched for a suitable beach to land on. With low swell predicted to drop even further, it was safe to consider some fun options that could be hazardous in other circumstances.

This marvelous and mysterious tunnel led to an curiously illuminated beach and is definately one of the neater landings I've ever made in a sea kayak.

After landing I took a moment to look over the rudder assembly to see that everything was still attached and functional. A rudder is a level of fuss and expense that doesn't usually make sense on a skin-on-frame kayak, even on a day tripping double, but for a touring, sailing, double it's a useful addition.

Our bow setup. The sail has a few strings but everything is clean and stows tidily. The fishing pole is kept ready for checking out those nearshore rocks that only kayakers can access.

A stunning campsite, albeit one of dubious legality and even more dubious tidal activity. There was some debate that we may actually be camping underwater.

Our view to the North. At first I was a little dissapointed with the fog and rain, but after a while it seemed appropriate to see this place against a palate of gray.

The entire headland is a giant rock swiss chesse and would be a marvelous place to explore with a whitewater kayak on a flat day.

Leann is happy to be cozy and dry!

Recieving over a hundred forty inches of rain a year in the coastal valleys, the Olympic Peninsula is an explosion of chloropyl.

Lush growth continues all the way to the tideline.

The next morning we discovered that no spoons had made it into our bags, luckily there were plenty of natural substitutes, already cracked open and well cleaned by the maurading raccoons that raided the rocks at low tide.

The mussel shells proved to be excellent utensils and caused one to wonder at the expense, effort, and pollution of making plastic or metal silverware.

Early morning revealed that our cave beach was now rock.

A few more hours brought the water back up to the sand though and after some stretches we were once again paddling south.

Well, paddling south for about 40 yards before stopping to explore this next cool cove.

As a connoisseur of fine coastlines across the globe I'm not quite sure how Cape Flattery has escaped me for so long. It's one of those things I always meant to do but just never got around to.

A typical scene on the Cape.

The entire trip we paddled in and out of heavy fog, which is quite manageable if not a little confusing, with a very low swell with no wind, but could easily become extremely dangerous with even a moderate swell and normal onshore daily wind pattern. The prediction of no wind and a falling 3ft swell for the first 3 days was the reason I chose to do this trip at all, and even then, the final decision wasn't made until the night before we launched.

You'd think we'd know better, but we packed the hats away. Of course the fog broke, neccesiting this tricky unpacking manuever miles from land.

A glassy flat ocean and a little help from some improvised water wings makes these shennanigans possible. By the way, yes, those are our life jackets piled on deck, and yes, if a tornado or a great white suddenly hit us we might be in real trouble, but considering the conditions it was much more comfortable without them. I would only do this on a dead flat day.

A two hour crossing brought us to a beautiful cove protected by two long reefs extending out to sea.

A relatively short 12 mile day and we were both tired which really surprised me. I thought that after a winter of hardcore whitewater paddling I'd be an animal, instead all that hard anerobic paddling made me less strong over the long haul, and of course I whined about it constantly. Leann kicked back while I dropped a line in search of dinner.

A few minutes of jigging and I reeled up this Ling Cod, which I promptly filleted on deck and stuffed the carcass into a crab trap. Decades of overfishing has brought a precipitous decline to the bottomfish populations of the pacific northwest, so nowadays the only fish I will retain are Ling Cod and Black Rockfish. While looking every bit as prehistoric and horrible as their spiniest rockfish bretheren, Lings are actually a different species that grow much faster and are much more resilient, Black Rockfish are also relatively resilient, although their numbers are a fraction of historic levels.

Barely a ripple penetrated the reefs and we glided to a calm landing on a pebble beach.

Leann spotted this marvelous little rocky nook, and the best part... cobbles! Anyone who has spent time camping on sand will tell you it is a vile and insidious substance to be avoided at all costs.

Priority number one: set up tent. Priority number two: Nap!

Who needs tent stakes? "Consider the advantage..." I told Leann, "If the tide does come up in the night, at least we'll know where the boat is!"

Just when you think you've found some privacy, the locals show up!

As the sun dipped lower we set out to explore.

Leann cooked us good food while I searched for meat to compliment the meals. Pesto pasta and fresh Ling Cod for dinner. (we didn't catch any crabs!)

Our spoons proved useful vessels for the after dinner drinks, and their precarity conviently limited our intake levels, in other words, when you can't hold the shell level anymore, you're cut off!

An idyllic evening scene on the Ozette coast.

Rather suddenly, we were beset by pea soup fog, this photo was take fifteen minutes after the photo above it.

Even with the tide right at the edge of our camp, I stubbornly refused to move the tent. I liked our little spot!

Leann is skeptical of the rising waters.

Does it seem a little weird to you that we hang our food in the trees to keep the bears from eating it, while we sleep on the ground....

Our not so big beach at twilight.

Morning rituals, breakfast, packing up....

...and filling the water bottles.

Almost ready to shove off.

We set out late in the morning toward Ozette island with a very low cloud ceiling.

We detoured a ways offshore to explore a couple little islands teeming with growling stellar sea lions. A loud snort and a splash close to the boat was enough to warn us off. It may seem ridiculous, but we're talking about a habitually aggressive animal the size of fully grown Rhinocerous. Anyone who claims not to be afraid of such creatures has not yet had one rise out the water five feet from ones face, snarling and shaking thier head and baring four inch long teeth. It's an instinctively horrifying feeling when you are sitting in a kayak. These are not seals.

The less choice real estate is left to the cormorants. I always feel bad for cormorants, often seen standing with open arms to dry their perrenially wet wings. Cormorants do in fact have oil secretion glands but unlike other sea birds, they don't seem to work very well.

The fog ceiling decended forcing us to paddle south close in through the nearshore reefs and kelp beds. This tactic was only made possible by the almost completely flat seas and lack of wind. The kelp made for slow going, but did afford us a magical passage through the treetops of these rich underwater forests.

Curious sea otters monitored our passing.

In the distance Leann spotted two bald eagles perched on a spire and we paddled over for a closer look.

We bashed into a few rocks working our way back out of the reef in the swell, but nothing damaging, and absolutely worth our intimate experience with the kelp beds.

Another hour of paddling and some irritating detours around long reefs brought us to what I thought might be a good landing place for the evening. The problem was that with no visibility, we had no way to be certain that we were indeed exactly where we thought we were, and exact is what is needed when you are talking about threading through breaking waves and reefs to hit a 100 foot wide sandy slot. Whereas more heroics and dicey recon missions are possible in a single kayak, the inherent sluggishness and unlikelieness of a successful combat roll in a tandem kayak means you have to be a lot more certain before committing. We decided to sit offshore and fish while we waited for a break in the visibility.

This positively enormous, (and positively unlucky) black rockfish is now headed for the deep six in the crab trap.

When the fog lifted I felt pretty proud that we were in fact exactly where I thought we were and all that was required was to land on this tiny sand hook, protected from the swell by a small curving reef. Much of this coast looks like a beach but is in fact a gauntlet of hard nearly submerged rock with a sloping beach above and behind it. With limited visibility such sights might tempt a kayaker to land in marginal conditions only to realize too late in the surf that there is no sand at all, possibly leading to less than pleasant outcomes.

We were soon engaged in the time honored tradition of salami, cheese, and triscuits. I was so happy to see the triscuits and greatly appreciated Leann bringing them instead of Rye Vita or some other such hippy dog biscuits.

Leann insisted that we bring Watership Down, a classic, extremely well written, and extremely boring book about an exodus of talking rabbits.

"I know it's going to suck." I said, "Nothing is going to blow up, and nobody has sex."

"Rabbits have sex." Leann countered.

I begrudgringly left the sci-fi at home, and predictably we trudged through about 15 pages of Watership Down in five days. Luckily we still have 200 hundred more pages to read on future trips. Do you hear that Leann? We're going to read the whole thing!

Feeling hopeful I headed back out to check the crab trap.

...and with dashed hopes I returned empty handed. I have never pulled an empty pot on a sandy beach and was feeling quite perplexed.

I suppose if thats the worst of your problems though, life ain't too shabby.

This entire coastline is managed by the national park service and while our trip may have been, um, less than officially sanctioned, I do try to keep within the spirit of their regulations by having no open fires and leaving no trace of our campsites. I have found it difficult over the years to coordinate touring on open coastines with governing agencies. With possible landings and schedules determined by the terrain and the mood of the sea, sticking to official campsites is often not possible. Still, I try to be respectful and keep a low profile.

After a dinner of rockfish fried in butter and garlic, and a few shells of single malt, we have strawberries and chocolate brownies for dessert.

A crack in the clouds gives us a glimpse of sunset.

The next morning we rise before dawn in hopes of early visibility and putting on some miles in a rising swell.

The little line of offshore rocks functioned exactly as I'd hoped, leaving us a small clean slot to escape past what were now significant waves thundering across the reefs.

Making miles before 7am. With the first pulses of a long period seven foot swell arriving, the breakers were anything but benign and we had to keep well offshore to avoid being dashed to splinters on the reefs.

Under beautiful skies we approached Jagged Island, a fantastic rocky pinnacle jutting up like a minature Tahiti. Even with the beautiful sunshine, I watched to the west like a hawk as a low lying fog bank snuck towards us, and to the east I constantly assessed and re-assessed possible emergency landing options through the now white and surging reefs. Five minutes after this photo was taken we were working our way slowly through some reefs when I saw Jagged island suddenly dissapear to my right. We made a quick decision to crash land on a semi-protected beach in the swell shadow of Jagged island, and after a dicey slalom through some boomers we touched down with a minimum of violence on a minimal beach.

This photo was taken ten minutes after the photo above it. We would not have been able to thread the reefs in this fog and just barely made it through them before everything went white. It should be noted that another option would be to paddle well offshore and head south on a known bearing for a known time and then hang a left for shore. This works well on less varigated coastlines with wide and less consequential targets. The North Washington coast however, is a minefield of offshore reefs and rocks that extends for miles offshore. After an hour or two of traveling a complicated course in zero visibility fog by compass and watch alone, with wind and current effects, even the best orienteering bad-ass might be a little intimidated to turn shoreward to hit a narrow landing target through reefs and boomers big enough to break boats and paddlers. Now consider that sea fog often comes with a 20+ knot wind and 6ft wind chop on top of whatever existing swell there is and you get an idea of the very real danger that exists in common conditions on this coastline. The point I am trying to make is that open coast touring, especially here, requires sound judgement and careful selection of conditions. Traveling should be limited to visible passages with a careful eye toward the ever present fog banks.

It became quickly apparant that our entire beach would be awash in the quickly rising tide, so we climbed over this ridge to consider the prospects of the next beach to the North.

This thin ridge connecting an small offshore pinnacle gave me the feeling of Macchu Picchu in the fog. We saw the next beach over to have slightly more real estate including a few cobbles, so we decided to punch out around the corner for greener, or um, grayer pastures.

Rather than wait for the tide to start sloshing us around with the driftwood we dragged the boat back to the tideline and headed around the corner.

Our new digs on the other side of the rock.

The mist blew in and out revealing errie glimpses of Jagged island.

We were barely settled when this curious young buck wandered down to see who we were.

With nothing else to do while the fog swirled in and out, Leann took a nap while I explored the beaches.

The beaches are always a facinating repository for various marine trash.

I especially liked this toilet seat cover.

I have no clue what this tiny thing and can only speculate it's the scalp of a member of a previously undiscovered secretive race of seven inch tall wild coast people. I know it's these little guys who stole my car keys, and my fork, and my bandanna, and my fillet knife, and my surf hood...

Twisted kelp mats stretched up the beach like an H.R. Giger painting.

The fog swept in and out but by the afternoon it seemed to be holding so we decided to try to make the seven mile hop to La Push.

Twice we passed by what I thought was a kelp bed and Leann thought were sea birds. We were both wrong, these were giant rafts of sea otters!

Even well offshore cutting behind the reefs to avoid mile long detours proved a sketchy proposition. I don't try to capture much of this action with the camera because it never looks all that exciting. For instance, the rock above is the size of a house for scale and exploded in mass of spray and fury every 10 seconds. Moments after this shot was taken we were lifted fifteen feet up by a set wave that was threatening to break on what we assumed was a deep slot. We punched the foamy white top and dropped into a series of menacing troughs as we sprinted hard straight out to sea!

Two miles from La Push in 5 knots of wind I asked Leann to raise the sail so I could get a photo. It's a wonderful little sail, made by Mick MacRobb of Flat Earth Kayak Sails. Easy to deploy, the lines and sail fold unobtrusively onto the deck, and doesn't actually need a rudder. I'm looking forward to using it to troll offshore for salmon this summer.

We paddle past little James Island on our way into La Push. The harbor here conveniently uses James and little James as extensions of their breakwater to create a navigable channel.

We paddle upriver against the current and into the marina...

...where we feel a bit shellshocked by the sudden contrast of civilization. We float aimless and indecisive for a few minutes looking for a place to tie up.

Not wanting to bother the absent harbormaster in this sleepy town we took a chance and just tied up inside the gas dock.

We stowed our expensive gear as best as we could and left this note for anyone who might come by. Some people might be apprehensive to leave so much gear unattended but I've found over the years that most people are more honest than you'd think. This being the the Quilleute Indian Reservation and me being a white guy, I supposed that even if the whole boat went missing I would just consider it reparations.

It was 6:30 pm and drizzling when we decided to embark on the 70 mile, 3 road hitchike back to Neah Bay. We set out with little more than street clothes and a quarter bottle of whiskey, figuring that at worst we might have an unpleasant night, but were not likely to die from it. Our first ride was the Quilleute shuttle, a free bus to forks!

Luckily they weren't enforcing the rules that day.

With the exception of the sunscreen caked onto my skin, we actually looked pretty tidy. I hitchike shuttles a lot and being clean and smiling is the first rule to getting a ride. You see a lot of hitchikers out there who look like Charles Manson, do these guys really think that they are going to get rides?

The shuttle brought us to 101, where we caught a ride north with a mountain climber who dropped us off on the very sleepy junction to 113. After walking this road for a half mile with no cars passing by we were starting to wonder if this was a bad idea when a Makah tribal councilman pulled over and gave us a ride to all the way to Neah Bay. Micah was a bright fellow and deeply involved in ocean resource issues so we had a lot to talk about on the long ride.

On our way out of Neah Bay we stopped to check out these impressive blue totem people.

Finally we arrived back at La Push at dusk, making for a very long day. Noone had bothered our kayak and we collapsed into a hard sleep feeling very grateful to have been lucky enough to see this beautiful stretch of coastline with favorable conditions, and a bit of luck when it mattered. The F2 prototype performed beautifully on the trip and it was a pleasure to use a tool so perfectly fitted to both the bodies of Leann and I and also customized for our needs. I think that this ease in changing even the hull shape for a single boat, even for a single trip, is what makes skin-on-frame so appealing to me. The challenge of course is knowing what to change and how to do it to achive a predictable result. Things don't always work out so well on a prototype, but in this case, everything functioned as intended which left me feeling pretty good. Kayaking for me is all about intimacy, the ability to get close to a remote coastline and really experience the place without a lot of fuss. A custom kayak takes that one step farther, allowing the kayak to dissapear as much as possible beneath you (but hopefully not literally!) so there is even less between you and the experience. This applies to any custom kayak really, skin-on-frame is just fun because it is such a fast, cheap way to get on the water. Even after building and helping to build well over 300 kayaks, I still get a lot of pride from saying I built it myself!

Back to Cape Falcon Kayak