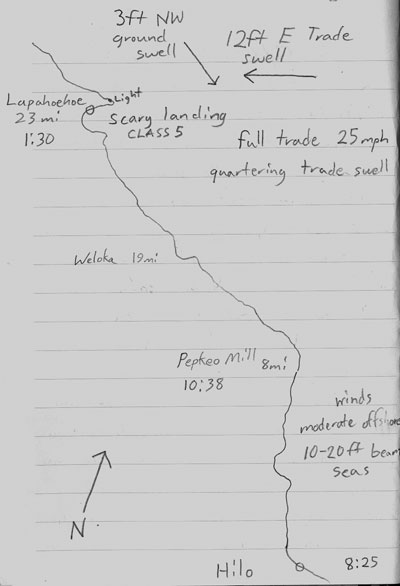

I paddle out of Hilo at 8:30 am on Monday and as soon as I clear the breakwall I fInd myself dipping into into 20ft beam seas, the remenants of yesterdays 30kt tradewinds. The shoreline is verdant and dotted with high waterfalls, this is the we side of the island. I push hard to get north eight miles around the bend where the coast parralels a course more in line with the direction of travel of the waves. I don't mind the seas but when the wind hits I want it as dead astern as possible, and when it does, I'm glad. I briefly fly the kite but the updrafts off the waves cause dangerously erratic flying and I decide that kiting downwind in a full 30 kt trade is a bit too exciting, even for me.

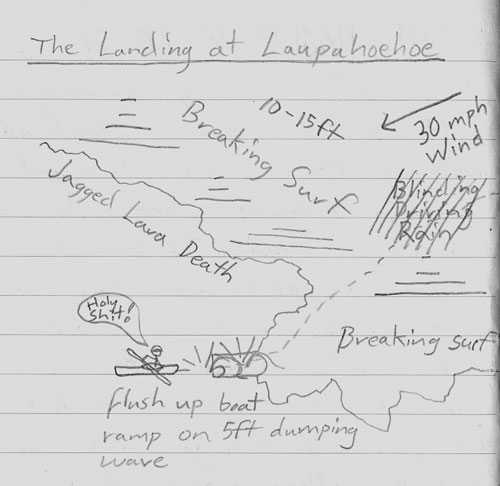

At 1pm I arrive at my only possible landing for this stretch, a small lava finger called Laupahoehoe sheltering a single tiny boat ramp. I approach Laupahoehoe in breaking 15ft seas, 30kt winds, and driving tropical rain. By all apperances the landing here would be accomplished one severed body part at a time. I knew there was a channel beneath the chaotic water, a clean slot, maybe eight feet wide, winding around the point and into the boat ramp. The problem is, the trade swell is blowing right up the mouth of my landing zone. The next landing was 27 miles north, so this is it. I have to ignore the intimidating mess on top of the water and paddle straight in where I know the channel is. The current wants to take me anywhere but in that slot, and on either side, it shoals into about a foot of water over the lava kayak-grater-of-doom. Have to stay on line. When I get a line of sight on the 'boat ramp' it's funneling waves into the parking lot that would slide back down into the sluice, creating a perfect six foot hydraulic on every wave. The current is ridiculous and I rely on power and a bit of luck to time the landing. I flush up into the parking lot, pop my skirt, and lunge out of the cockpit and paste as much of my body to the ground as possible, relying on friction to keep from getting sucked back.

I stand for minute and look back at the route in. Helmet, elbow pads, PFD, I look more like a gladiator than a sea kayaker. An onlooker asked me,

"How dangerous was that, what you just did?"

"We call that Class 5 sea kayaking." I replied.

Rich came up to visit me that night . "Dude!" I exclaimed as I led him to the boat ramp, "I thought you said this was a safe landing."

"It is," he rebuffed, "but I've never seen it like this before."

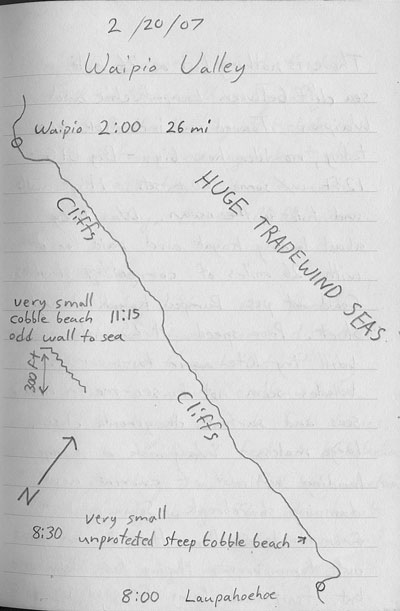

Regardless, I thought it went pretty well. I feel solid and strong. At 8am the next morning I peel out into the trade seas again, running with the seas almost dead astern as I trace the coast northwest toward the Valleys. This next section is the single most homogenous shoreline I've ever toured. A two hundred foot high, twenty six mile long sea cliff. Todays highlight is the seas themselves. The tradewinds blow uninterrupted for thousands of miles creating a fifteen foot sea, but those waves travel at slightly different speeds, combining with themselves and with yesterdays seas. The net effect is that every fifteen minutes or so a thirty foot set rolls through and I'm looking down into a hole in the ocean large enough to park a suburban house in. The scale is spectacular, a wave the size of a two story house rolling under me every five seconds.

The danger in these seas, I'd soon come to realize, is not the waves but near collisions with surfacing humpback whales that several times almost come up right beneath the kayak.

I round the corner to Waipio valley at 2 pm. Surfing 20ft wind waves around the point does little to instill confidence in my ability to land here. Luckily the valley is just deep enough to bend the wind swell enough to knock down it's energy. I'm tempted to push for the next, more remote valley, but there are people here and instinct tells me this is the right place to land. Again, I nailed the landing and pulled ashore with a minimum of violence. I set up camp, hanging my hammock in the the trees.

The scale of the waves, the whales along the way, and now this mile wide and almost sheer walled tropical valley. I half expect a forty foot iguana to step through the foliage and snap me up. I take a hike up to the north ridge on a trail that is essentially a staircase.

I sleep fitfully that night. The next day I'd planned to round Upolu point, the northern most tip of the island where winds might exceed 50knts in the trecherous Alenuihaha channel seperating the Big Island from Maui. This was a crux section but I felt strong and was looking forward to linking this coast with Kona. By sunrise I'm really tired though so I decided to break the day up and try for Keokeha a marginally suicidal landing twelve miles to the north. I crawl back in the hammock and begin to feel ill.

By noon I'm delerious, completely in the grips of some horrible sudden illness. It takes perhaps a half hour for me to put on my sandals, and maybe a hour just to stuff my gear in the boat. I'm utterly feeble. My legs are like wooden logs and I staggered for all I'm worth toward the nearest road. My legs are exposed to the sun and turning red, I have sunscreen but the thought of applying it seems appallingly difficult. Everything I do is acompanied by a verbal command. "Okay, we can do this, ready, right leg forward, left leg forward, don't trip, good, right leg forward..." I reach the road and collapse. I lie there sweating like a Malaria victim, sprawled across the road until parks workers are kind enough to scrape me into the back of a truck and deposit me at the top of the 25% grade road out of the valley where I desperately beg a ride back to Hilo with some visiting fisherman from Alaska. Back in Hilo I can't get a cab because a cruise ship had taken up all the available ground transportation so instead Rich walks me to the hospital and checks me in with a 103.6 degree fever. I moan in agony and my body feels like it's being crushed in a vice. I think the other emergency room patrons were ready to kill me by the time the doctors hook me up to an IV containing liquid antibiotics and painkillers. They send a nurse in to inject my IV tube with a fat syringe of clear liquid, an exteremely strong painkiller called Dilaudid, and he starts slowly injecting it while watching my vital signs. I watched the monitor as my blood pressure and pulse drop, it feels like I'm being euthanized. I apologise to the nurse. "I'm sorry, I know I probably should have just slept it off, but it just hurt so much." He looks up at me. "No man, you need to be here, you're really sick." This is the first time anyones told me that. "How sick, I mean, I'm not going to die am I?", he pauses for a minute, "We don't think so." Now there is scary answer if I've ever heard one! Rich kindly keeps me company. I talk to him for a while and then he answers while I nod off, my mouth hangs open and drool pours out the side (from the Dilaudid), we repeat this strange conversational mode for hours.

For the next two days my fever held above 102. Eight days later I ate my first full meal.

So thats it, the anticlimactic climax of my great Hawaiian adventure. These are the things we can't possibly plan for and I'm bummed because of how hard I trained and how well I was doing on the paddle. This trip was ill-fated from the start though, the ridiculous quantity of gear failures I experienced, my cameras' death, Rich's bad feeling, and finally the sickest sickness I've ever experienced. Honestly, I left the island not caring if I ever return, but I'm hoping that with time, I'll find my way back with a new camera to finish the voyage and write the story and see the best parts of the island that I was saving for last.

Until then, I go back to work, building kayaks all day every day, in the wet and frigid Oregon winter. Not the worst thing I guess.

Back to Cape Falcon Kayak