Hawaii, putting in the miles

on the Kona Coast.

2/12/07 - 2/17/07

Rich drives me to South Point where currents and winds from the

Kau Coast and the Kona Coast accelerate and collide in an impressive

washing machine. On some

days, Rich tells me, the confluence is so violent that the waves stand

up in fifteen foot spikes of water, the whole mess sweeping out toward

Tahiti. We scope the spot from a fascinating cliff called

'broken landing' where Rich tells me to watch the dog (again,

what am I supposed to DO exactly?), and then dives 30 feet down into

the most beautiful blue water I've ever seen. He climbs

back up on a rope.

Looking north from Broken Landing.

I

launched my new SC-1 kayak, freshly painted with shark

repellant stripes, into a mild trade wind swept sea, only twelve foot breaking

waves. I rounded South Point and headed north, clinging to the

shoreline and tucking in tight behind low cliffs dropping into the

clearest deep blue

water I've ever seen. The effect was hypnotic and I remember

thinking,"It would be ok to drown in this water."

My

moment of natural awe was quickly replaced with natural terror when

two miles later a fin a little bigger that a dolphins fin surfaces ten

feet in front of

my kayak. My mind grapples, "what is wrong with this fin?".

Three distinct things, it didn't breathe, it didn't dive, and it turned

sideways. SHARK, BIG SHARK the alarm sounded inside me, it

would NOT be ok to be eaten

in this water! I countered the rising panic with a powerful

message

forced backwards through my nerves to the tips of every mollecule and

capilary, DON'T. FREAK. OUT. A dark boil erupts next

to me and then it's gone. Was it a shark? The chances say

not likely, but it was an odd fin that set the stage for how

I would respond were I to see another.

I paddle five miles north from broken landing to a large

natural lava pyramid fronted by a red sand beach and a small dumping

wave. Rich calls this place 'the Great Eye'. It's desolate

and utterly devoid of vegetation. A pair of Humpback whales cruise by

at sunset. I put on

my 'Destination Wear' Kokatat pants and shirt, exquisitely well

designed quick dry garmets that made me feel like a kayaking

commercial. They really are damn comfortable clothes.

My camera dies completely after this photo. Wind howls across the

beach all

night. I sleep in my hammock tied up against a low lava cliff.

2/13/07

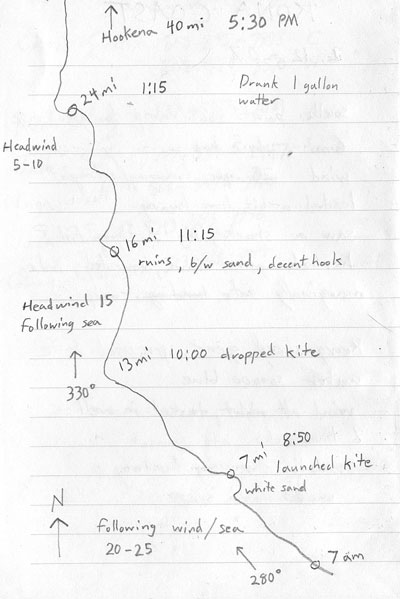

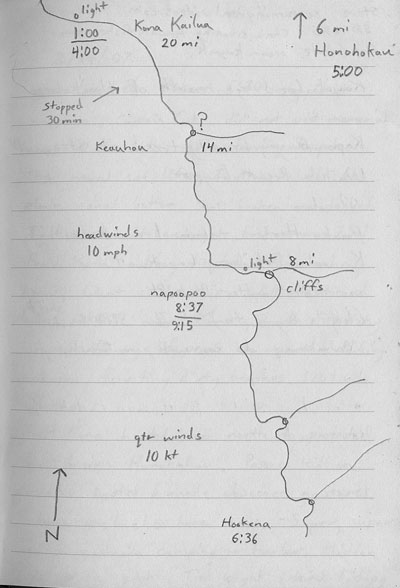

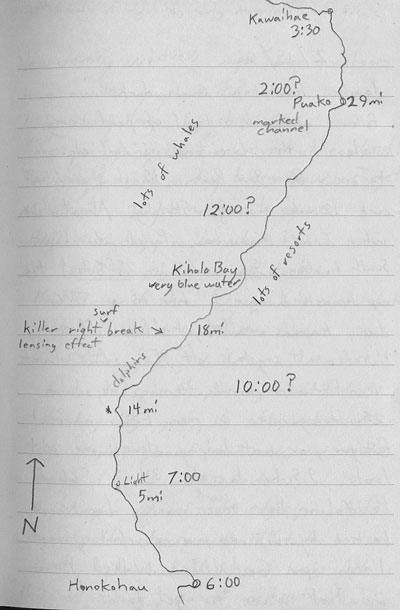

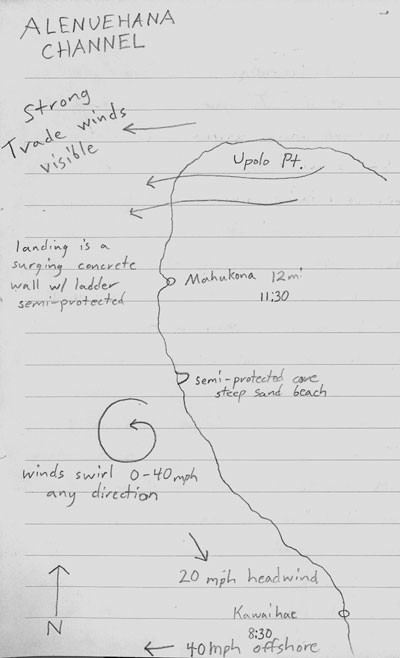

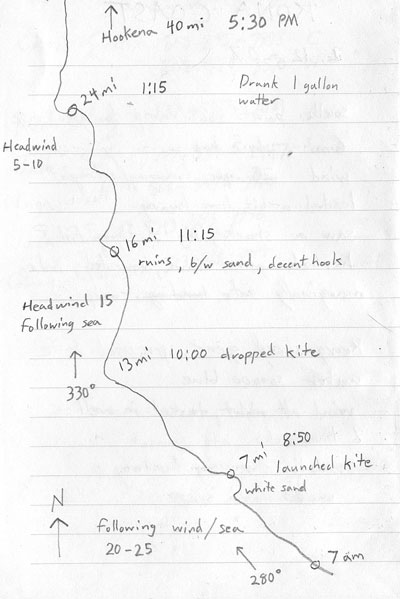

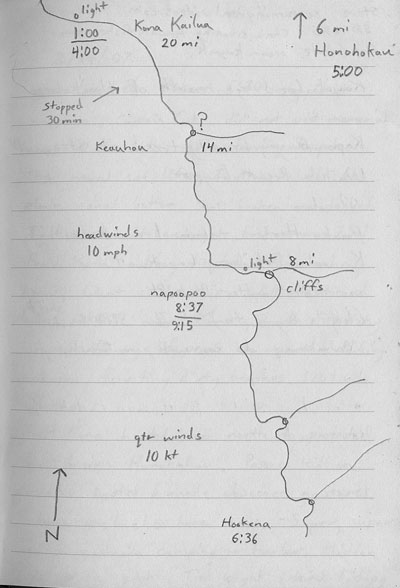

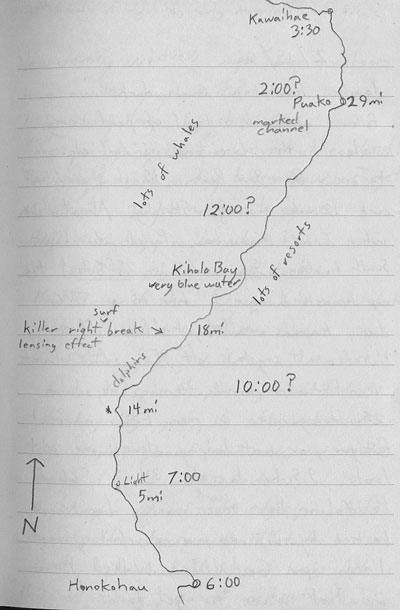

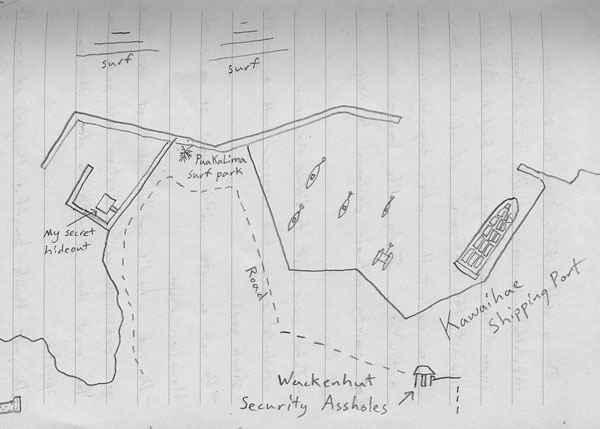

To navigate open coastlines I now prefer a diver's white board

to a chart case and china markers. At night I trace the map for

the next day adding just the information I need. During the day I

track my progress directly on the map, adding notes and using the

backside to write notes from anyone I might meet on the beach or the

water. The system is compact and accurate for point to point

navigation. At night I trace the maps back to my journal.

Morning inventory, day two, I no longer have my second set of

sunglasses, my knife is missing, and my $1000 DSLR camera has given up

the ghost. Not good, the physical currents may be with me but the

'unseen forces' are beginning to flow opposite my course.

At dawn I load the kayak and push

it out through the

surf. It's easier to swim a kayak out in small dumping

surf. The sun rises behind me. Paddling

north along south Kona is alot like touring in parts of Baja. Low

volcanic cliffs, desert scrub, little habitation. The difference

is the half mile wide black lava flows that stretch upwards to the high

slopes of Kiluea, large rivers of hardened molten rock that once

poured down

into the sea every five miles, erasing all vegetation to the

shoreline. The first sign of habitation is the remote Hawaiian

village of Miloli, built directly onto one of these flows it's roads

appear impossibly steep, the front porch of each house is in some cases

the roof of the house below it. It seemed an unlikely choice for

a village except for the small beach that fronts it, a rare gem on

this rock studded coastline.

At 1pm I'd been paddling for

twenty five miles and I was at the edge of my chart where I'd marked,

Hookena 15mi N. There was still plenty of daylight and what was I

going to do all afternoon sitting on a

tiny beach? I decided to paddle for Hookena. A few miles

out to sea I paddle up to a small motor boat piloted by a ragged long

haired white guy in shorts and a dirty flower print shirt.

Surprised to see this apparrition of a kayaker,

he hauls up a single tiny yellow fish on a longline baited with dozens

of hooks before pointing me toward Hookena. I thought back

to the book The Curse of Lono where in this very spot Hunter Thompson

drops a note in a bottle into the sea that reads simply, 'There are no

fish'.

I paddle onward, pleased that after three months of grueling

training I feel strong and comfortable at thirty miles. I'm

precise with my rituals on the water, my hydration pack feeds up

through my spray skirt supplies a steady drip of electrolylte at one

quart per ninty minutes. Every hour and a half I eat a cliff bar

(Cliff bar refused to sponsor my expedition by the way), and every

three hours I

stop for five minutes to consume an energy gel packet and apply

sunscreen. At thirty three miles I run out of food and

water which is a bad thing because as soon as you stop eating and

drinking your body stops burning fat and starts using liver glycogen,

which takes five days to replenish. (Now you know why

you were so tired after that last camping trip). I'm pushing my

limit when I arrive at Hookena beach, a tiny hook of sand backed by

cliffs, palms, and a small parking. A dimunative and friendly

bearded man named

Jim approaches me "Welcome Ashore!" I've been paddling alone on a

quiet sea for ten and a half hours and due to the calorie depletion I'm

totally freaked out. Jim seems like a bellowing giant. I do

my best to act

normal as I set up camp while a pretty old lady keeps trying to feed

me rice cakes. I stare at the rice discs like flying saucers

while I tick off all the camp chores, packing tommorrows food and

eating cold cereal for dinner, nursing the little water bags off the

mother water bags, making the map.

"Do you have a permit to camp here?" Oh if I had a dime for every

time I've heard that. Closely followed by my spiel about being on

an expediton and not being able to plan day to day. This park

ranger wasn't buying it and she basically ordered me back into the

ocean. I had to be direct. "It's dark, I paddled forty

miles today, there are big sharks out there, and there is nowhere to

land for twenty miles." "You have to leave now." she

responded. "Look," I implored, "I can't leave, it's not possible,

it's not going to happen. So you do whatever it is you need to

do, I'll be right here." It reminded me of the moment when

I was six years old and I refused to eat liver. Sometimes

when you are resolute in the face of authority you'll discover that

authority has no real power. At other times you are arrested and

jailed. This ranger didn't want to do the paperwork and simply

left me alone to sleep on the sand. I quietly slipped into the

sea at first morning light.

2/14/07

Eight miles north I pass Napoopoo, the site where Captain Cook was

killed in a scuffle with the natives who were no longer conviced he was

their

returned God Lono. I don't paddle over the monument. I've

read about it in exhausting detail and in essence, I've already been

there. Instead I slip on my fins and mask and slide over the side

into the clear blue water. Pulling the kayak with my tow belt,

for a half hour I follow colorful fishes and slow motion turtles across

the rocky bottom before climbing aboard and paddling onward.

At mile twelve I pass a scuba diving boat called 'Kona Aggressor

2', which makes me wonder what happened to the Kona Aggressor

1.

Houses begin to dot the shoreline as I near the city of Kona, vacation

capital of the Big Island. With the city still in the distance I

spot a sit-on-top kayaker and change course to intercept. An

Alaskan native, Steve has beek kayak fishing for big game fish here in

Kona for six years. He sits high on a chair in his kayak with a

cooler strapped to the back deck and a fishing rod trolling behind

him. He chain smokes while I deluge him with questions

about the coastline ahead

as we drift together. He cautions me, 'Even when you check the

weather, even

when you do everything right, I've had days here where I've paddled out

and it's just the trail of tears trying to get back.' We're

now in the shadow of two massive 13,000 ft volcanos, where severe

catabatic winds sweep down off the slopes without warning. From

here North people do get blown out to sea. A week earlier Chris

told me, "I used to fish out there with an EPIRB duct taped to my

chest."

From the sea the city of Kona speaks for itself. High on the hill

above a bustling and kitchy downtown filled with sunburnt vacationers

pretending to have fun, sits two behemouth icons of American

consumerism,

Wall Mart and Lowes. When I actually

land there I like it even

less. I eat a twenty dollar sandwich and return to my

kayak. I pass a monstrous cruise ship in the harbor. These

corpulent floating cities discharge massive amounts of garbage and

sewage directly into the worlds oceans. I despise their existence.

A half hour before sunset I round the westernmost tip of the island and

for once I have company. Surfskis and OC-1's slice past me

on a race course. Some are piloted by children seperated from any

adults by a mile or more, no PFD's or myriad of gear. Just paddle

and paddler. I have no doubt these children could swim the

miles back to safety if neccesary. I pass a group of young

teenagers playing on the low lava cliffs above me and think to myself

how picturesque they look in the low evening light. Then the

start hooting and laughing, making exagerated masturbation

gestures. It takes a moment to sink in, they're making fun of

ME. I shout obscenites back

at the fourteen year olds, which

just just makes their taunting more vigorous, and makes me shout

louder. Hey, they started it! Then

I realize they have rocks to throw and I don't, so I paddle away from

my

impotent position below.

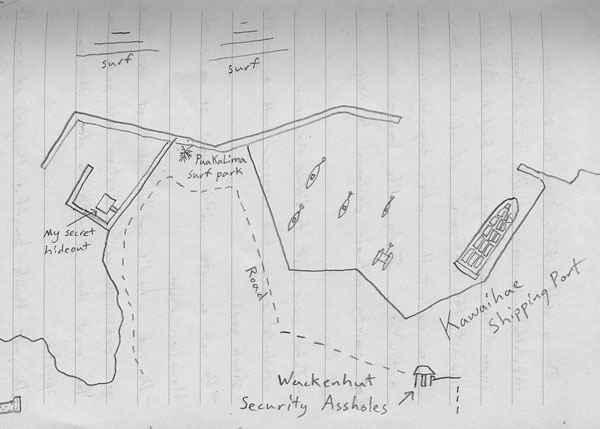

At sunset I paddle into Honahokau, the only protected small boat harbor

on

the entire island. A few hundred yachts and sport fishing

boat are crammed into this tiny harbor, moored bow to bouy, stern to

shore. I'm leary after last evenings encounter so I choose

subterfuge as my camping mode for the night. Finding a

secret place to camp here is a creative enterprise, I have to

analyze all the lines of sight trying to find a place to hide in plain

sight. I end up tying my boat to the stern of a shiny white sport

fisher named Huntress. There is no shore, and I can't step into

the sea urchin encrused spiney rocks. The only access to shore is

a small wooden landing five feet above sea level. I sit on the

back deck of the kayak and carefully balance while unloading my gear

through the cockpit. The real trick is setting the paddle as an

outrigger and standing up on the back deck and lifting the gear onto

the landing, and then lunging up onto the platform and quietly

unpacking in this bustling marina. Luckily I'm not

discovered. In the dark of night sea turtles terrorize little

schools of little fish causing watery eruptions.

2/15/07

It's dark when I paddle out of Honohokau harbor at

6am. I follow a compass heading toward a headland I should be

able to see soon, and as it always does, the sun slowly draws shapes in

the twilight of dawn. I rise and fall gently with the swell,

following more of the ubiquitous low lava cliff shoreline. My

body aches a bit and I don't feel very solid in the mornings. It

takes about fifteen miles to get my groove going, I settle into the

kayak better and my body mechanics become automatic. On deck is

one of my old paddles that belongs to Rich. The shape is common,

shorter and wider, I use it to push off from rocks near shore. In

my hands in the new shape I've been pulling since last October.

Only 2 3/4 inches wide and 88 inches long, this stick with it's sharp

edges has the cleanest pull of any Greenland paddle design I've used

yet. I gives good power with minimal joint damage and I can push

hard for long distances day after day with it.

The kayak is nice too, fourteen feet long with a thirteen foot

waterline, a blunt swedeform hull with generous flare above the

waterline. This kayak glides easily at cruising speeds and

doesn't fuss too much in a quartering sea. At 23 inches wide it's

rock solid stable with a gear load which is nice when you plan to be on

the water for thirty four miles. At at steady

4mph I've been averaging my best cruising speeds ever in this stubby

little kayak. Sculpted wooden thigh hooks have been added

which gives me a much more solid grip on the boat. Loading the

large cargo float bags and sliding them in and out is a snap and that

is very nice after touring in ultra low volume kayaks for years

now. I've

been hesitant to say much about the

new boat without testing it personally, but by now I've decided I can

safely tell people I like it.

In Kihola bay the water is electric blue and I paddle past some

beautiful remote beaches that I probably should have stopped to camp

on, but what can I say, I'm a pusher, and so I pushed onward. A

pod of dolphins passed through me, their quiet inhalations are soft and

beautiful. At mile twenty I break away from the land for a

long crossing in a notorious wind tunnel between the saddle of Mauna

Loa and Mauna Kea. Based on weather reports and a hunch I thought

I could chance it. Many kayakers prefer to trace

coastlines, but I'm a semi-pelagic creature and I'm happy to paddle

away from the shore.

Out here in open water 40 ton humpback whales dominate the scenery, and

not just a few, there are literally dozens of whales swimming and

frolicking offshore here. They seem to intuitively keep a

distance of about 100ft from the kayak. I don't chase them, but I

don't alter my course to avoid them either. In one intance I

observe a whale beating it's massive tail against the water and assume

that it will notice my approach. I realize I'm mistaken when the

tail explodes from the water thirty feet from the bow. BANG,

BANG, BANG, the huge fin and body thump the water. Note to self:

stay away from the tail slapping whales.

I stroke steadily toward the distant port of Kawaihae, a large

industrial harbor that never seems to get any closer. At mile

thirty I hit the wall, I'm literally cooked. The

sun had been out all day with no clouds or wind and the lack of cooling

sucked my energy harder than expected. The calm wind held and I

completed the crossing, feebly stroking into an abandoned breakwater,

on the edge of the harbor. Surrounded by a 100ft square of

stacked rocks, this isn't exactly most peoples idea of a camping spot,

but I've always liked the places nobody else visits and this small man

made lagoon held a very special treasure.

Parked right in the middle of this empty, desolate little harbor was an

off-white 22ft square carpeted, padded dock, the ideal guerilla

campsite. When I coasted to a stop at it's soft edge my kayak

blended perfectly with the color. This was the perfect

place to sort and re-sort gear. No pesky sand or rocks.

Despite my constant energy bars and electrolyte, I was shaking and

dizzy when I flopped myself onto the carpet. Note to self:

restrict future paddles to 30 miles or less. Crunch! I

stepped on my sunglasses, the price of inattentiveness and paddling for

too long. I stripped off my kayaking gear and hiked to a nearby

road, and then walked to a restaurant for dinner. Oddly enough,

this evening stroll on the highway is proabably the most dangerous part

of my entire journey. Hawaii has the nations highest pedestrian

fatality rate.

2/16/07

The fifth day I stay put as wind strong catabatic winds blast down off

Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea. I surf a solid 10ft swell at

sunrise, the fifteen foot faces are intimidating to say the

least. Just like the paddling here it takes solid knowledge and

total commitment, because once you go, you gotta go. Hesitate and

you get bombed. I don't hesitate. At sunset the wind

dies enough to surf the falling swell again. I find myself caught

inside (between a wave and a jetty) as a rouge set comes through. I'm

out of adrenaline so I'm just thinking, matter-of-factly, 'I gotta get

outside' as I paddle steadily for the

walls of water, cresting the first, then the second with a bit of a

slap out the backside, and finally the third flatwalls as I paddled

hard up the face. I press my paddle and head hard to the deck and

pierce the lip, opening my eyes as I exit the back of the wave into a

blood red sky, hang in mid air, and splash down.

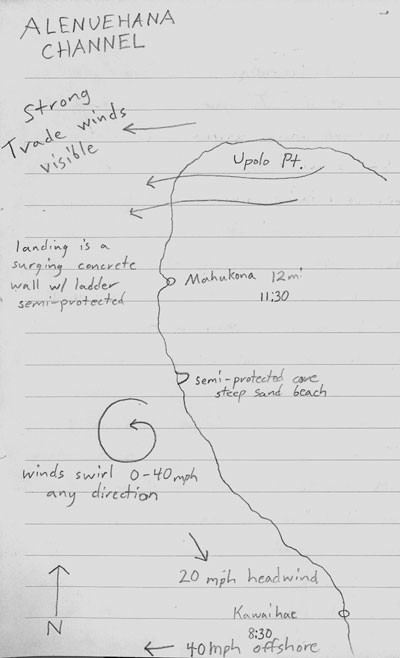

2/17/07

The next day I paddle out into the same 40mph crosswind and fight hard

to keep from being blown out to sea, playing a dangerous game as I

paddle north, flirting with the cliffs and reef to hide from the

wind. I reach my landing at Mahokena to discover that it is

nothing more than a surging concrete wall with a ladder going up.

Getting my kayak and

gear up it is an adventure. Rich meets me

and we drive back to Hilo, scoping out the intimidating Hamakua (north

east) coast. My paddle on the Kona side was a cakewalk compared

to the next two coasts, Hamakua (north) and Kau (south), both exposed

to the full force of the trade winds. Hamakua is home to

the Shark Gods, and Kau home to Pele, lava flowing into the sea.

Tommorow I rest in Hilo and prepare for what I came here for, with

luck, the island and the weather will cooperate. It's hard to

temper my ambitions without being able to see the landing sites.

The ground swell is only 3 feet, but the trade wind swell is 12

feet. Each coast is sixty miles long with only one possible

landing every 20-30 miles. I've never feared big wind chop, but

the

trade swell is really big

wind chop and my lack of experience with it creates

unknown factors. I don't like unknowns. I'll do as much

scoping as I can tommorrow to prepare for a launch and attempt the

north coast on Monday.

Kayaking the Hamakua Coast